-

![LANG-CODE-KEY]() LANG_NAME_KEY

LANG_NAME_KEY

A new year means new stuff! As well as plenty of shiny new things for you to enjoy in World of Warplanes throughout 2014, we are also pleased to introduce a new series of articles called ‘Technical Focus’.

Ever wanted to know how a plane actually works and flies, but have been put off by complex jargon and tons of maths? With this occasional series, we’ll explain it all in plain language and you’ll become an expert in no time!

For this first article, we take a look at…

Most of the planes in World of Warplanes are propeller-driven. Indeed, until the invention of the jet engine towards the end of World War II, propellers were the only technology available for driving a plane forward.

The propellers of World War II and earlier are much the same as the propellers in use today on light aircraft. Perhaps you have travelled across Europe on one of these:

Bombardier Dash 8 – a medium-range turboprop passenger plane, used by many small European operators. The power source is different, but the actual propeller is much the same.

Propellers are also still the principle means of propulsion for ships and boats of all sizes, from tiny speedboats to huge battleships.

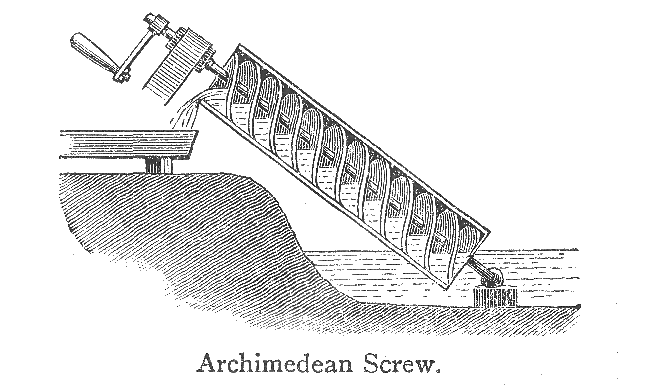

It is unclear when the propeller was first invented. Variations on the theme have existed since the time of Archimedes (Greece, approx. 250 BC). He proposed a screw design for lifting water for irrigation.

Archimedes envisioned the screw being used for moving water from one place to another. However, the principle also works in reverse – keep the water still and it is the screw that moves. This principle can easily be illustrated with a familiar household device – the corkscrew!

|

Once the cork has been removed from a bottle with the corkscrew, it will remain stuck on the screw. Hold the cork tightly and twist the handle – the corkscrew itself will move as it is forced out of the cork. Now imagine that your corkscrew is the Archimedes Screw in the image, and the cork is the water. If the water is treated as a huge motionless single object (i.e., an ocean), it is the screw that will be forced to move as it is turned and whatever is attached to the screw will move with it. |

While Archimedes only applied the principle to water, the concept of using the same idea for making vehicles fly through the air was considered by another prominent historical thinker:

This sketch by Leonardo da Vinci dates back to the 15th century. You can see the resemblance to Archimedes’ Corkscrew.

This sketch by Leonardo da Vinci dates back to the 15th century. You can see the resemblance to Archimedes’ Corkscrew.

So how do we get from a screw to a propeller? The answer is in the curved nature of the propeller blades.

|

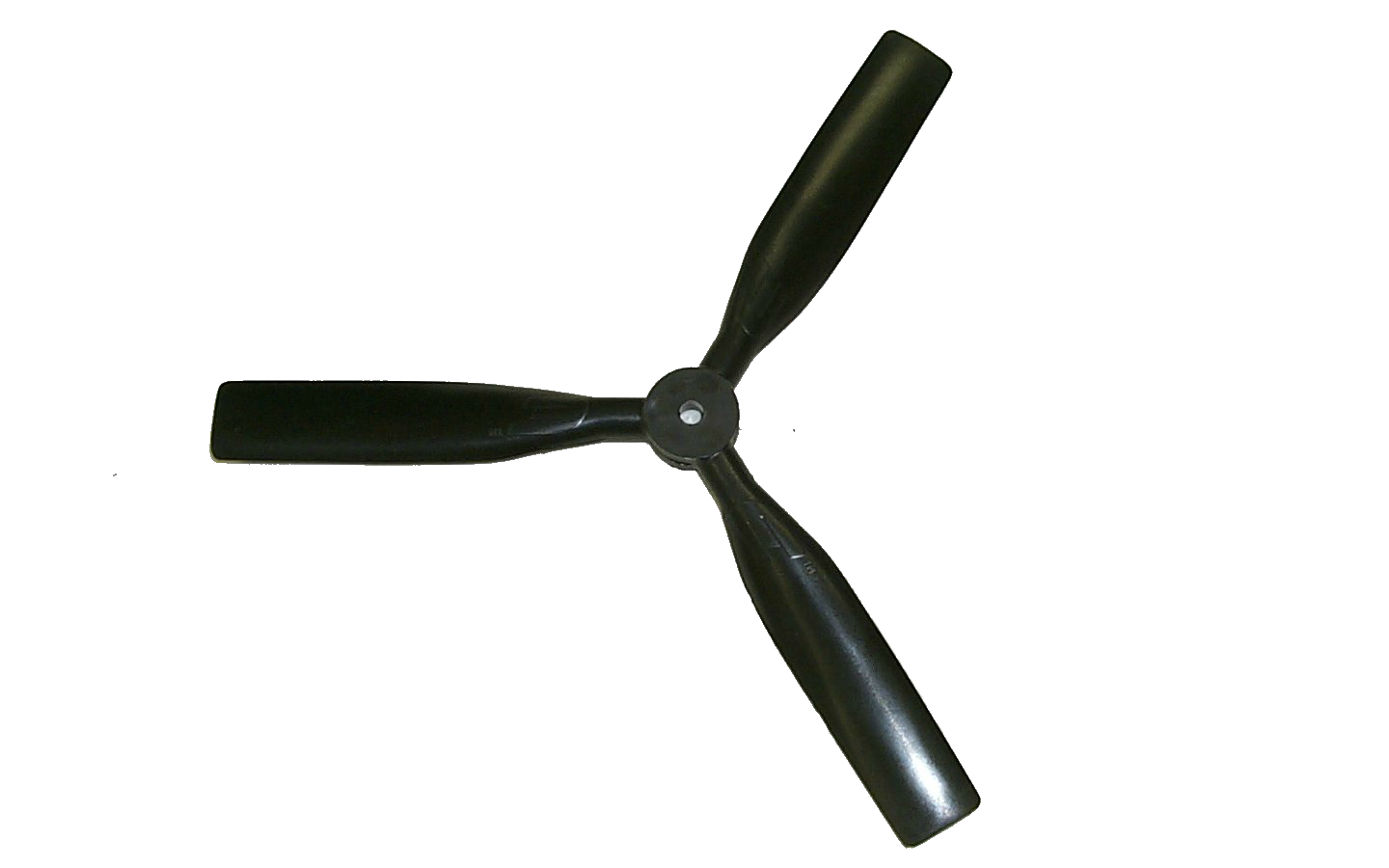

Typical marine propeller. This one is made from bronze. Marine propellers usually have anything from three to six blades and can range from a few centimetres in diameter to several metres.

|

|

The curvature of the blades mimics the thread of the screw. As the propeller turns, the curvature forces the water backwards, creating an ‘opposite and equal’ forward force on the propeller itself called thrust – just like the corkscrew. This thrust causes the object attached to the propeller to move forwards.

The first true mechanical ship propellers emerged in the early 1800s. A hundred years later in 1903, the Wright Brothers worked on and adapted the principle in order to move an aircraft.

Early thinkers such as da Vinci envisioned the propeller being used to lift the aircraft. However, in a plane it is the wing arrangement (called an aerofoil) that creates the lifting force, which will be the subject of a future article. This meant that the Wrights only needed the propeller to provide forward motion for the plane, just like a ship. As a result, one of the main tasks in designing their first aircraft was to work out how to convert the propeller arrangement used on water-going vessels to provide thrust through the air.

In very basic physics terms, water and air are both fluids. As a gas, the air has a far lower density (the ratio of mass to volume) than water, and this heavily affects the properties required of a propeller. The Wright brothers realised that for an aerial propeller to exert thrust in the way that a marine propeller did, it was rotation speed that made the difference. They figured out that the plane propeller would need to consist of long thin blades to cut through the air at speed, rather than the short, wide ones used for pushing through water.

|

Typical aerial propeller. Compare this with the marine propeller above. You can see that the blades are long and narrow, the better to cut through the air and provide thrust at high speed. |

The curvature of the blades is also designed carefully. The twist in the blade is shallow at the tip and deeper towards the centre. This ensures that the thrust is even across the blade. This is important because, when rotating, the tip moves at a much faster speed than at the hub.

|

The end result is that the propeller pulls the plane forwards through the air. How fast it goes is completely dependent on the design of the propeller and the power of the engine that is turning it. The first Wright Brothers aircraft flew at a speed of just 6.8 miles per hour (11 km/h) – approximately the rate at which a human can gently jog. Just a few years later, planes were already exceeding 100 miles per hour (161 kilometres per hour) thanks to improvements to propeller and engine design.

Turboprop engines were designed in the 1950’s as a means of combining turbojet technology with a propeller. In these types of engines, the jet engine is used to turn the propeller rather than eject the energy as a stream. They are much more efficient at lower speeds, and so are often used in smaller short or medium distance aircraft such as the Dash 8 shown at the top of this page. Nonetheless, the basic functioning of the propeller is exactly the same as in the older combustion engine variety used in the planes in World of Warplanes.Throughout the early years of flight (until near the end of World War II), the engines were all standard combustion engines powered by petrol or diesel. The introduction of the jet engine at the end of World War II very quickly rendered traditional propeller engines obsolete. A jet engine doesn’t use a propeller at all – the thrust is provided by the high energy jet stream ejected by the engine. However, the propeller didn’t vanish for good. |

|

Now you know how it works… go and get airborne, pilots!