-

![LANG-CODE-KEY]() LANG_NAME_KEY

LANG_NAME_KEY

There is no breathable air, at the same time the sun is searing your skin with intense radiation it would also freeze due to the extremely low temperatures; gas bubbles would begin to form within your circulatory system, you might even feel the saliva in your mouth and the moisture on your eyes turn to steam before you expired. Mankind is not naturally equipped to traverse the outer reaches of the Earth’s atmosphere, but with the dedication and perseverance of more than a few individuals we’ve secured a tenuous ability to explore the space around our planet, and consequently, we’ve developed methods for returning should things go amiss.

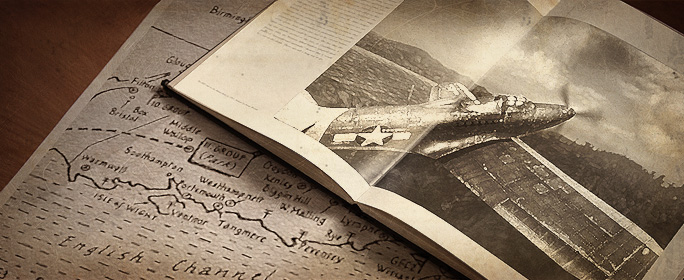

In the 1950s the jets were able to carry their pilots to exceptionally high altitudes at great velocities, a new era of aviation had been born, but until research like that conducted first in Project High Dive, then in Project Manhigh, and finally in Project Excelsior, there wasn’t enough scientific data available to develop emergency systems for those high flying pilots.

On the morning of August 16, 1960, Captain Joseph Kittinger donned a pressurized suit ladened with sensors for his third Project Excelsior jump; he rode in an open gondola below an enormous helium balloon to an altitude of 102,800 feet (19.4 miles). On the way up the pressure seal on his glove failed. As he gained altitude his hand swelled up to twice the normal size, causing him great pain, but he chose not to tell mission control until he was at jump altitude because he didn’t want to abandon the mission. Prior to the flight, a placard was secured at the lip of the gondola that read “This is the highest step in the world”. Kittinger took that step.

He was in free fall for 4 minutes and 36 seconds. At the beginning of the jump, from his vantage point, he couldn’t be sure that he was falling, there was no sound, there was no rippling of the fabric on his suit, as there was no air to cause it to flutter; there was only the rounded blue edge of the planet at every horizon and the balloon rapidly retreating from vision. Shortly after starting the descent a drogue chute deployed to lessen the chance that he’d go into an intense spin on the way down. It succeeded in stabilizing him, and after passing through miles of atmosphere achieving a top speed over 600 miles an hour and finally cratering through the clouds, the main chute was deployed at 17,500 feet. It took 13 minutes and 14 seconds from the time he left the gondola until he was returned to earth.

While the goal of this project was only to gather scientific data, Kittinger set the world record for the highest ascent of a manned balloon, the record for the longest free-fall, and the highest parachute jump—all obtained in this one mission. The information gathered from Project Excelsior enabled the development and refinement of safety systems for pilots of new age high altitude aircraft. The same technology and understanding gleaned from those experiments keep our pilots that much safer today.

He had the support and knowledge of an entire team behind him, but it was only one man that took that final step. Extraordinary volunteers, like Joseph Kittinger, are often overlooked or dismissed as ‘crash test dummies’ when compared to some of the inventors and pioneers of aviation, but it’s both dreamers and daredevils that extend our reach further and further beyond the surface of planet Earth.