-

![LANG-CODE-KEY]() LANG_NAME_KEY

LANG_NAME_KEY

At the start of American’s involvement in World War II, fighter tactics reflected the lessons learned during the first world war: the secret to winning was to out-turn your opponent using the maneuverability of your fighter to get into firing position on your opponent’s tail.

This held true, to a certain extent: getting on your opponent’s “six o’clock” was the best way to shoot him down. The Japanese seized upon this in the design of the A6M “Zero” fighter, a lightweight and highly maneuverable fighter. During the early stages of the war in the Pacific, it seemed like a wonder weapon; allied P-40s, P-39s and Brewster F2A Buffaloes all suffered when their pilots tried to fight turning battles against the Zero.

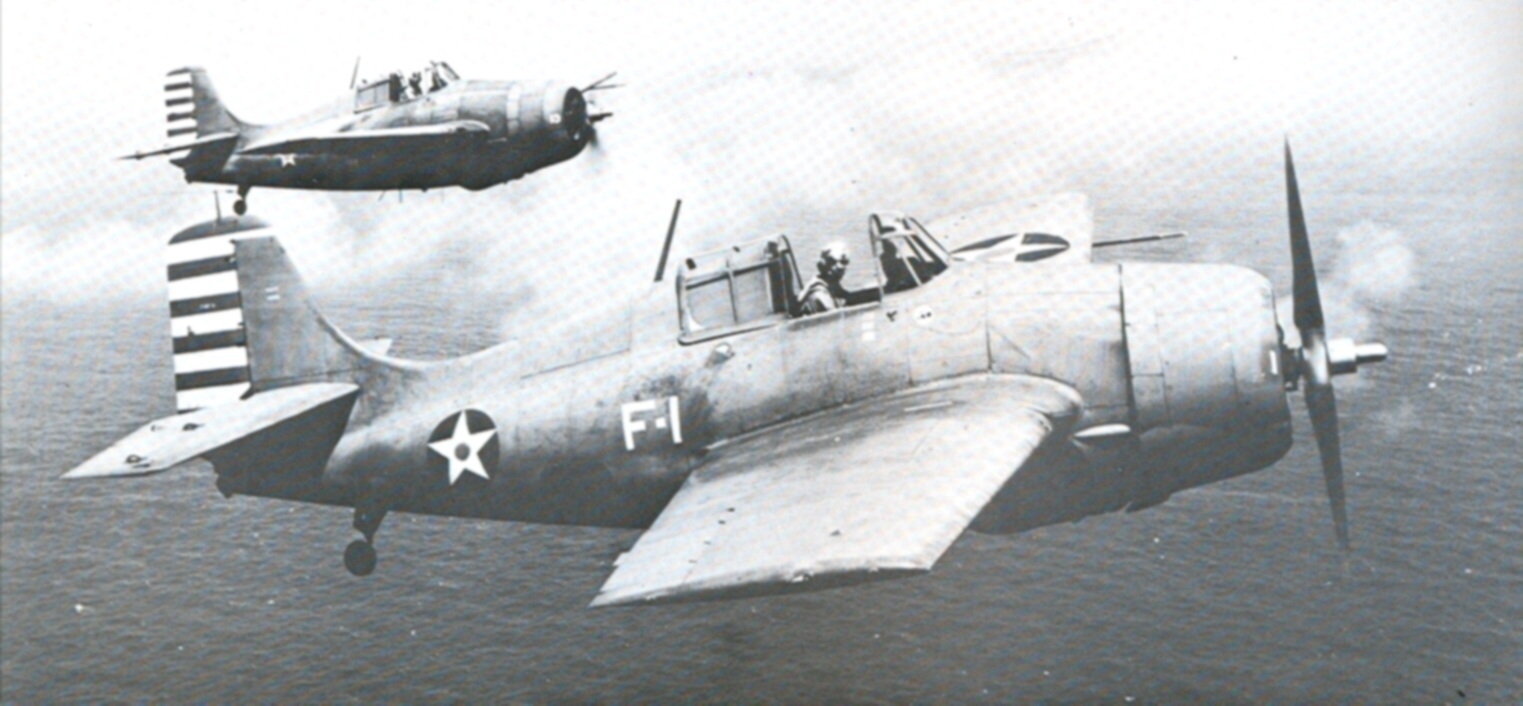

The Navy suffered similar issues with the F4F Wildcat. It didn’t have the maneuverability of the Zero, and with additions like self-sealing fuel tanks, folding wings, and two extra .50-caliber machine guns in the F4F-4, the Wildcat was even less able to turn with the Zero. “It was like flying with your pockets full of cement,” said Tom Cheek, who was a chief machinist flying with VF-2 aboard Hornet in the spring of 1942.

Countering the Zero would require new tactics. Experience would gradually reveal that the A6M’s fabric-covered control surfaces ballooned with air at speeds above 295 mph, making it hard to turn the aircraft. That meant fighting the Zero at high speeds was a good recipe for success. It was also discovered that the Zero was fragile – a good burst often started a fatal fire or caused terminal structural damage.

But in May 1942, that was not yet known. While many clung to pre-war fighter tactics, Jimmy Thach, was thinking about new ways to battle the Zero. He’d been thinking about it since 1941, when the first intelligence on the Zero had been sent to fleet squadrons. The traditional defensive tactic for fighters was the Lufbery circle, or a turn entered into by a formation for mutual support. Since the Zero could out-turn the Wildcat, it could get inside the circle and pick apart the defenders.

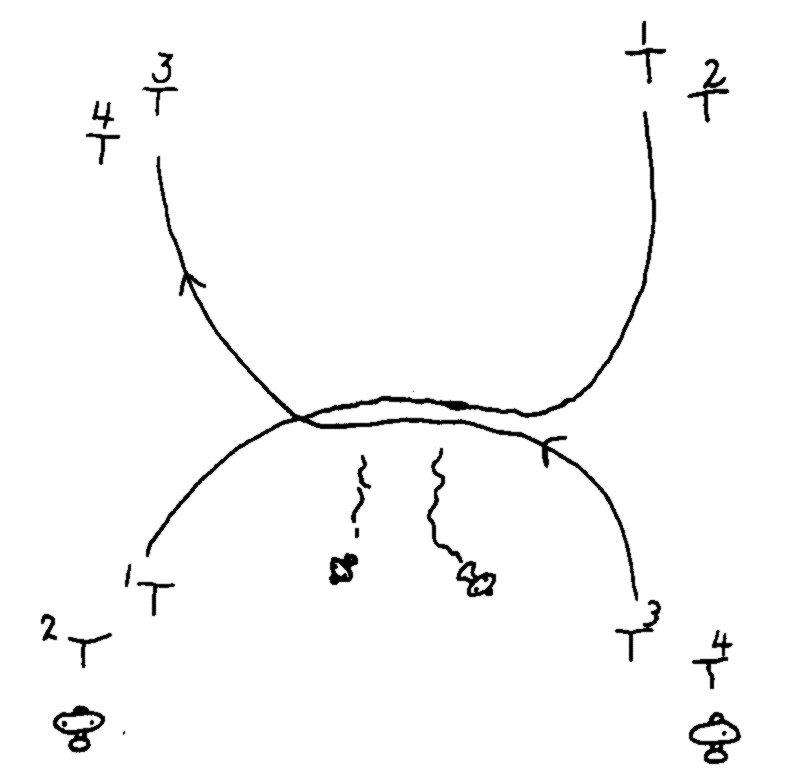

Thach wanted a formation that was defensive, but could also put his fighters on the offense. He devised a maneuver called the “beam defense maneuver. In it, he positioned the two sections of his four-plane flight abreast if each other at a distance equal to the turning radius of the Wildcat. In the event a Zero jumped on the tail of one section, the two sections would turn toward each other, setting up the second section for a head-on shot at the attackers of the first section. If the attacker turned away, it then had the second section on its tail; if it turned into the second section, it put the Wildcats in position to repeat the maneuver.

Thach first tried out his tactics with VF-3, with the adversary section led by future medal of honor winner Edward “Butch” O’Hare. Try as he might, O’Hare could not set up a shot; he found it disconcerting to line up a target, only to have it swerve away at the last minute and have two other fighters rushing at him head-on.

Thach never had a chance to test the maneuver with VF-3; during the raids on Lae and Salamaua on March 10, 1942, no fighters rose to challenge the navy planes. In April, most of VF-3’s pilots were transferred to other units and Thach had to build up the squadron from scratch.

In early May, Thach took up three of his first new men – Ens. Robert A. M. “Ram” Dibb, MACH Doyle C. Barnes and MACH Tom Cheek – and taught them the beam defense maneuver. After some practice, Thach arranged for two P-39s from the 78th Pursuit Squadron to play the role of Zeros. Again, the attackers couldn’t gain position, and often the Wildcats found themselves in firing position.

The maneuver, which became known as the “Thach Weave,” found its baptism of fire on June 4, 1942 at the Battle of Midway. Thach hoped to take two flights in escort of Torpedo Squadron Three, but was given only six planes: a full flight, consisting of Thach, Dibb, Lt. Brainerd Macomber and Ens. Edgar “Red Dog” Bassett, and a partial flight, with Cheek and Ens. Daniel Sheedy. Nearing the Japanese fleet, Thach’s flight was bounced and Bassett’s trailing F4F-4 was hit, slanted toward the water and burst into flames. Macomber’s plane was stitched by fire as well, but the rugged Wildcat kept flying. With three planes, Thach’s section first fell into a line-abreast formation and started dodging Zeros individually.

Zeros were making attacks every 20 to 30 seconds. Thach’s Wildcats and the Zeros were scissoring back and forth, taking snap shots at each other. One Zero pilot missed a snap shot at Macomber and slowed up to correct his aim; Thach slid in and shot down the A6M2b for his first victory of the battle.

Macomber had not been instructed in the weave maneuver, and his radio was out, so Thach called to Dibb and told him to act like a section leader. Dibb slid out wide to the right of the other two Wildcats and the Zeros quickly pounced on the lone American fighter. Dibb radioed for help and turned back toward his two wingmen; Thach turned into him, and Macomber followed dutifully. Thach dipped under Dibb and bore in on the Zero; the Japanese fighter shed part of its cowling and burst into flames.

Dibb swung back into line abreast formation, not knowing what Thach wanted, but it finally dawned on him that the weave required him to move out and to the side. Zeros tried to attack, and were brushed off by the weave; most simply broke off their attacks, while others pressed their attacks and paid for it. Thach destroyed a third Zero when it tried to follow Dibb through the weave, and Dibb claimed one of his own. Even Macomber shot up a Zero, although in frustration he broke formation to chase the Japanese plane, gaining credit for a probable.

The Thach weave soon became doctrine and served Wildcat pilots well over Guadalcanal and the Solomons, and even later as the faster and more maneuverable Hellcat and Corsair came into fleet service. It would become a standard fighter maneuver, and it was even used by Phantoms in the Vietnam War when confronted by the more nimble MiG-17.

Cheek’s section also tangled with Zeros; for a first-hand account of Cheek’s battle, and his tale of learning the Thach weave, check out this interview here: http://www.internetmodeler.com/2002/june/aviation/Cheek.htm